Thursday, August 30, 2007

Life and Limb 2005

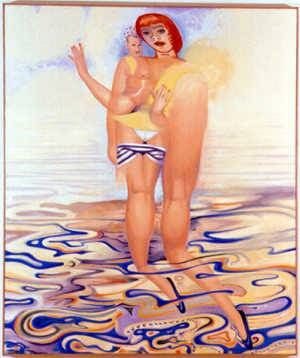

Life and Limb, curated by David Humphrey at Feigen Contemporary

June 3 – July 30, 2005

The world is lousy with threats and dangers! It's amazing that we aren't paralyzed with dread. We're good, though, at telling stories that both assuage and kindle our fears. Life and Limb is a story about those stories. Narrative figurative art has flourished throughout history, from prehistoric cave paintings to digital images beamed into space. This exhibition will trace an eccentric itinerary through various regions of modern and contemporary art. Prints, drawings, paintings, photographs, sculptures and videos will survey various matters of psychological urgency through depictions of figures doing things with and to each other.

Narrative can be purveyed by any media in an astonishing variety of genre. Like brain function, narrative is deep. We don't understand anything without connecting cause to effect, past to present and future. A story uses memory and imagination to organize sense data into something coherent. Because narrative artworks can only represent a fragment, or part of a continuum, the viewer must imagine the before and after based on what's presented.

Life and Limb focuses on intersubjectivity, on what people do and feel between each other. Acts of resistance, surrender, conflict, love, sex, longing and phobia drive narrative operations in general as well as the works in this show. Some artists picture a sanctuary from these conditions while others drive straight into the darkness; some adopt a comic stance while others get serious.

Do we choose to believe the words of the off-frame speaker in Kerry James Marshall's print who asserts, "Everything will be alright. I just know it will"?

To see images from the exhibition, click here.

Oven Stuffer Roaster 2005

Turkey Cone Installation at Morsel Gallery, Brooklyn, NY

Read about it and see more pix at jameswagner and bloggy.

Wednesday, August 29, 2007

Lonely Tylenol 2003

A collaborative book project by David Humphrey and Sharon Mesmer, published by Flying Horse Editions, Florida

Click here to read more.

Tuesday, August 28, 2007

Monday, August 27, 2007

Sunday, August 26, 2007

Hi, My Name is Artwork 2000

Artworks can be inconvenient, often making conspicuous efforts to go against the grain. Other times they are more sociable, working hard to insinuate or ingratiate. Whether artworks adapt postures of detachment or engagement, an ineradicable quotient of ambiguity intensifies their vitality. They are, often happily, only human.

The artist's signature, along with the work's material characteristics, inflects the way it navigates and adapts to a future of unanticipated circumstances, much as we do. Alternating positions of resistance, assimilation and participation help us to thrive in different situations. This applies to the course of a day as well as the arc of a lifetime. We assimilate in order to study unfamiliar situations and learn how things work. Sometimes we don't want to be noticed. Resistance builds strength and sharpens our sense of distinction while cooperation rewards us with a connection to others. Who doesn't want to be successful? Freedom from necessity is a recurring dream and art is good at exercising a vision of this freedom. Artworks help us to imagine what freedom looks like and consequently help us to resist the status quo.

New art, for a very long time, has caused things to mean what they hadn't meant previously. It can conjure fresh meanings from familiar forms and render the perceived world like a hallucination. Art can symbolize or symptomatize contradictions and tensions in the culture and can juggle various ratios of conformity and deviance. New art has also thrived on its ability to produce confusion, sometimes for progressive ends and sometimes in the service of mayhem and disorder. Works based on deviant attitudes adapt well to the latter while eventually, perhaps, helping to serve the ever fluctuating use of style to sell consumer products. Art objects still address only one person at a time, and are lucky if they can produce confusion or any strong reaction whatsoever with their shocks and postures.

We artists should not underestimate the importance of the stories we tell ourselves about how art will make a difference. These motivational fictions describe the ways a work might interact with the world to justify our extravagant, and potentially narcissistic, labors: that our art has transformational potential. A work might be understood as being critical of society or that it provides sanctuary from it, for instance, or that the work is like a Trojan horse sent to the enemy as a nasty gift to unsettle their deeply entrenched frames of mind. We need renewable encouragement to make fresh work year after year in the face of uncertain rewards. Political art glows with these motivational fictions no matter how much we may disagree with the editorial content. Paranoia provides one of the most effective sources of motivation. That's why a notion of the "spectacle" has been so engaging for artists in the last few decades. The spectacle is described in theory as everywhere, with no boundary to its insidiously embracing circumference. It can replace deity as the ubiquitous and invisible force that catches us in its address and through which our public utterances are addressed. It neither confirms nor denies our ascriptions but compels us to continue undermining its grand perniciousness.

I don't think artists are reliable, however, at making their work socially useful. Some will be more responsible than others, but the work's capacity to survive depends on its ability to produce engaging interpretations whenever and wherever it finds itself. Do we want to be good citizens or servants of a system we may or may not approve of? The inconvenience that artworks present to pragmatic or utilitarian attitudes provokes both resentment and hopefully unanticipated insight.

The meaning of an artwork is promiscuously slippery, ambiguous and, like artists, not very dependable. Contexts come and go while attitudes within the work often seem to evaporate or shift. The U.K. has recently been embracing new art as an instrument of public policy to promote "diversity, access, relevance, civic pride, community innovation and social inclusion." A recent show at the Met of Renaissance art from Delft had many examples of astonishingly beautiful art that beamed with unambiguous civic pride. Does collectively embraced new art necessarily satisfy an appetite to feel good about ourselves? Works we love often seem to aid insights that come from us, not necessarily about ourselves but issuing from our best self. These special works seem to have significance above the others by virtue of their capacity to bring us a heightened sense of our singularity on the shared plane of culture. Some works almost seem to reorganize themselves as we change over the years; they grow with us and share our power to resist and assimilate.

I feel the artwork's relative uselessness is one source of its enduring radical value. Maybe that's my motivational fiction. If we can't be outside the spectacle, at least our metaphors will continue the always unfinished job of imagining and desiring an outside, that perhaps things are more mutable than we thought.

The artist's signature, along with the work's material characteristics, inflects the way it navigates and adapts to a future of unanticipated circumstances, much as we do. Alternating positions of resistance, assimilation and participation help us to thrive in different situations. This applies to the course of a day as well as the arc of a lifetime. We assimilate in order to study unfamiliar situations and learn how things work. Sometimes we don't want to be noticed. Resistance builds strength and sharpens our sense of distinction while cooperation rewards us with a connection to others. Who doesn't want to be successful? Freedom from necessity is a recurring dream and art is good at exercising a vision of this freedom. Artworks help us to imagine what freedom looks like and consequently help us to resist the status quo.

New art, for a very long time, has caused things to mean what they hadn't meant previously. It can conjure fresh meanings from familiar forms and render the perceived world like a hallucination. Art can symbolize or symptomatize contradictions and tensions in the culture and can juggle various ratios of conformity and deviance. New art has also thrived on its ability to produce confusion, sometimes for progressive ends and sometimes in the service of mayhem and disorder. Works based on deviant attitudes adapt well to the latter while eventually, perhaps, helping to serve the ever fluctuating use of style to sell consumer products. Art objects still address only one person at a time, and are lucky if they can produce confusion or any strong reaction whatsoever with their shocks and postures.

We artists should not underestimate the importance of the stories we tell ourselves about how art will make a difference. These motivational fictions describe the ways a work might interact with the world to justify our extravagant, and potentially narcissistic, labors: that our art has transformational potential. A work might be understood as being critical of society or that it provides sanctuary from it, for instance, or that the work is like a Trojan horse sent to the enemy as a nasty gift to unsettle their deeply entrenched frames of mind. We need renewable encouragement to make fresh work year after year in the face of uncertain rewards. Political art glows with these motivational fictions no matter how much we may disagree with the editorial content. Paranoia provides one of the most effective sources of motivation. That's why a notion of the "spectacle" has been so engaging for artists in the last few decades. The spectacle is described in theory as everywhere, with no boundary to its insidiously embracing circumference. It can replace deity as the ubiquitous and invisible force that catches us in its address and through which our public utterances are addressed. It neither confirms nor denies our ascriptions but compels us to continue undermining its grand perniciousness.

I don't think artists are reliable, however, at making their work socially useful. Some will be more responsible than others, but the work's capacity to survive depends on its ability to produce engaging interpretations whenever and wherever it finds itself. Do we want to be good citizens or servants of a system we may or may not approve of? The inconvenience that artworks present to pragmatic or utilitarian attitudes provokes both resentment and hopefully unanticipated insight.

The meaning of an artwork is promiscuously slippery, ambiguous and, like artists, not very dependable. Contexts come and go while attitudes within the work often seem to evaporate or shift. The U.K. has recently been embracing new art as an instrument of public policy to promote "diversity, access, relevance, civic pride, community innovation and social inclusion." A recent show at the Met of Renaissance art from Delft had many examples of astonishingly beautiful art that beamed with unambiguous civic pride. Does collectively embraced new art necessarily satisfy an appetite to feel good about ourselves? Works we love often seem to aid insights that come from us, not necessarily about ourselves but issuing from our best self. These special works seem to have significance above the others by virtue of their capacity to bring us a heightened sense of our singularity on the shared plane of culture. Some works almost seem to reorganize themselves as we change over the years; they grow with us and share our power to resist and assimilate.

I feel the artwork's relative uselessness is one source of its enduring radical value. Maybe that's my motivational fiction. If we can't be outside the spectacle, at least our metaphors will continue the always unfinished job of imagining and desiring an outside, that perhaps things are more mutable than we thought.

Friday, August 24, 2007

Describable Beauty 1996

One of the inglorious reasons I became an artist was to avoid writing, which, thanks to my parents and public school, I associated with odious authoritarian demands. I found the language of painting, in spite of all its accumulated historical and institutional status, happily able to speak outside those constraints. Of course language and writing shade even mute acts of looking. The longer and more developed my involvement with painting became, the more reading and writing freed themselves from a stupid super- ego. Writing about art could be an extension of making it. But there persists in me a lingering desire to make paintings that resist description; that play with what has trouble being named. I was recently asked to speak on a panel about beauty in contemporary art and found myself in the analogous position of speaking about something that I would prefer to resist description. Describing beauty is like the humorlessness of explaining a joke. It kills the intensity and surprise intrinsic to the experience. I found, however, descriptions can have more importance than I originally thought.

The rhetorical demands of defining beauty often lead to ingenious contradictions or sly paradoxes. It's amazing how adaptable the word is to whatever adjective you put before it; radiant, narcotic, poisonous, tasteless, scandalous; shameless, fortuitous, necessary, forgetful or stupid beauty. I think artists have the power to make those proliferating adjectives convincing based on what Henry James called the viewer's "conscious and cultivated credulity." A description can have the power to prospectively modify experience. To describe or name a previously unacknowledged beauty can amplify its possibility in the future for others; it can dilate the horizon of beauty and hopefully of the imaginable. To assume that experience is shaped by the evolution of our ingenious and unlikely metaphors is also helpful to artists; it can enhance our motivation and cultivate enabling operational fictions; like freedom and power. We are provided another reason to thicken the dark privacy of feeling into art.

Loving claims are frequently made for beauty's irreducibility, its untranslatability or its radical incoherence. André Breton ardently said that "convulsive beauty will be veiled erotic, fixed explosive, magical circumstantial or will not be." Henry James defined the beautiful less rapturously as "the close, the curious, the deep." I think that to consider beauty as the history of its descriptions is to infuse it with a dynamic plastic life; it is to understand beauty as something that is reinvented over and over, that needs to be invented within each person and group.

Beauty's problem is usually the uses to which it is put. Conservatives use beauty as a club to beat contemporary art with. Its so-called indescribability and position at a hierarchical zenith makes beauty an unassailable standard to which nothing ever measures up. This indescribability, however, is underwritten by a rich tangle of ambiguities and paradoxes. For critics more to the left, beauty is a word deemed wet with the salesman's saliva. They see it used to flatter complacency and reinforce the existing order of things. Beauty is here described as distracting people from their alienated and exploited condition and encouraging a withdrawal from engagement. This account ignores the disturbing potential of beauty. Even familiar forms of beauty can remind us of the fallen existence we have come to accept. When beauty stops us in our tracks, the aftershock triggers reevaluations of everything we have labored to attain.

Finding beauty where one didn't expect it, as if it had been waiting to be discovered, is another common description. Beauty's sense of otherness demands, for some, that it be understood as universal or transcendent; something more than subjective. Periodic attempts are made to isolate a deep structural component of beauty; articulated by representations of golden sections, Fibonacci series, and other images of proportion, harmony and measure; a boiled down beauty. Even in the most unexpected encounters with the beautiful, however, there coexists some component of déjà vu or strange familiarity. To call that experience universal or transcendent performs a ritual act of devotion. It protects the preciousness one's beauty experience in a shell of coherence. I think there are strong arguments for beauty's historical and cultural breadth based in our neural and biologically evolved relation to the world, but arguments for artistic practices built on that foundation often flatten the peculiar and specific details that give artworks their life. The universalizing description also overlooks the work's character as a rhetorical object, subject to unanticipated uses within the culture. It draws people toward clichés and reductive stereotypes which are then rationalized as truths and archetypes.

If I have any use for the idea of beauty, it would be in its troubling aspect. I was describing to a friend my mother's occasional fits of oceanic rage during my childhood, and she told me I should approach beauty from that angle. Like mothers, I suppose, beauty can be both a promise and a threat. All roads eventually lead back to family matters. Perhaps this path to beauty begins to slant towards the sublime; to that earliest state of relatively blurred boundaries between one's barely constituted self and the tenuously attentive environment. Attendant experiences of misrecognition, identification, alienation and aggressivity during early ego development become components of the beauty experience. The dissolving of identity, the discovery of unconscious material in the real, a thralldom of the senses underwritten by anxiety, are a few of my favorite things.

If there is a useful rehabilitation of beauty in contemporary art, I think it would be to understand it as an activity, a making and unmaking according to associative or inventive processes. Beauty would reflect the marvelous plasticity and adaptability of the brain. I'm tempted to go against the artist in me that argues against words and throw a definition into the black hole of beauty definitions; that beauty is psychedelic, a derangement of recognition, a flash of insight or pulse of laughter out of a tangle of sensation; analogic or magical thinking embedded in the ranging iconography of desire. But any definition of beauty risks killing the thing it loves.

Published in New Observations

Tuesday, August 21, 2007

Monday, August 20, 2007

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)